The Mystery of the Shroud

A Comparative Study of Shīʿī and Sunni Reports

Introduction

What was the Messenger of Allah shrouded in? Not an inconsequential question for Muslims who seek to model all aspects of their lives on that of a man whom they consider their exemplar par excellence.

A strange thing happens, however, when one begins to dig into this seemingly innocuous question, for there exists a great disparity of answers preserved in the sources depending on the authority one consults.

This paper attempts to investigate the most probable answer to this question, but in doing so a metaphor emerges that depicts the reality of where it all went wrong for the umma!

A few Terms

It is important to clarify the meaning of two important Arabic words that will recur throughout the paper before proceeding:

- Ḥibara cloak – A famous striped and embroidered cloak made in Yemen.[1]

- Ṣuḥārī garment – A garment made in Ṣuḥār, a town in Yemen.[2]

Many Answers

The fact that the early historian Ibn Saʿd (d. 230) felt compelled to set-up three consecutive chapters in his voluminous Ṭabaqāt[3] to record all the different answers given to this question demonstrates how highly contested it was.

The degree of contradiction between the statements of the companions is such that the tābiʿī Abū Qilāba (d. c. 104) exclaimed:

Don’t you wonder at them (i.e. the companions) differing to us over the shroud of the Messenger of Allah?![4]

I will not review all the different answers here, but it seems to me that there are, in practice, only two horses running in the race: The answer given by the prophet’s cousin (ʿAlī) versus the one given by his wife (ʿĀʾisha).

I will take up one after the other.

The Background

The earliest biography of the Messenger of Allah, that of Ibn Isḥāq (d. 151), contains the following account of the Prophet’s ghusl which Ibn Isḥāq received from a number of his informants[5] who ultimately attribute it to Ibn ʿAbbās:

ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib, al-ʿAbbās b. ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib, al-Faḍl b. al-ʿAbbās, Qutham b. al-ʿAbbās, Usāma b. Zayd, and Shuqrān, the mawla of the Messenger of Allah, were the ones who gave ghusl to him.

Aws b. Khawlī, one of the Banī ʿAwf b. al-Khazraj, said to ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib, ‘I implore you, O ʿAlī, in the name of Allah and our share (i.e. the Anṣār) in the Messenger of Allah (to permit me)!’

[Aws was from the companions of the Messenger of Allah and one of those who participated at Badr]

He (i.e. ʿAlī) said, ‘Enter!’ so he (i.e. Aws) entered, sat down, and witnessed the ghusl of the Messenger of Allah.

ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib made him (i.e. the Messenger) lean upon his chest while al-ʿAbbās, al-Faḍl, and Qutham would be helping him (i.e. ʿAlī) to turn him (i.e. the Messenger). Usāma b. Zayd and Shuqrān, his mawla, were the ones who poured water on him. ʿAlī washed him having made him lean upon his chest and while he (i.e. the Messenger) was still clothed in his qamīṣ (shirt). He (i.e. ʿAlī) would rub him (i.e. the Messenger) with it (i.e. the qamīṣ) from the outside, not touching the Messenger of Allah with his hand directly.

ʿAlī kept saying, ‘How good you are both in life and after death!’

It was not seen from the Messenger of Allah what is usually seen from a dead body (i.e. decomposition)[6]

Ibn Isḥāq follows up this account of the ghusl of the Prophet with a report from ʿĀʾisha who claims that those involved in the washing of the Prophet, whom she tellingly does not name, argued with each other over whether they should undress the Prophet before his ghusl or not. They are then put to sleep via divine intervention and a voice instructs them to wash him ‘with his clothes on him!’[7]

ʿĀʾisha concludes wryly:

If I had known then what I do now none would have washed him except his wives![8]

This reveals a certain tension that existed between the blood-relatives and the wife over who controlled the Prophet’s highly symbolic final rites and the narrative around it.

- The Prophet’s Cousin

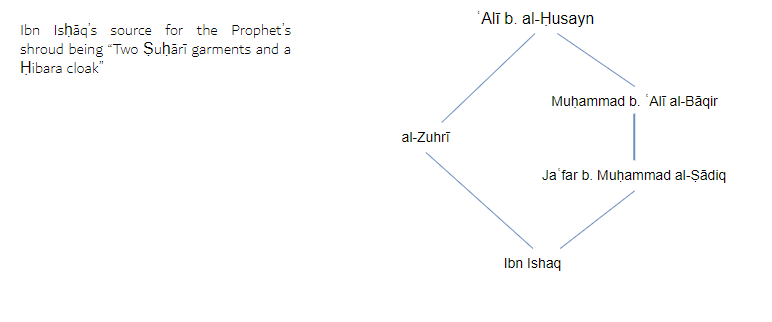

Ibn Isḥāq moves on to the shrouding of the Prophet and for this he turns to the report of the prominent Alid: ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn (d. 95).

So when they were done with the ghusl of the Messenger of Allah, he (i.e. the Messenger) was shrouded in three garments: Two Ṣuḥārī garments and a Ḥibara cloak, one wrapped over the other.

This was narrated to me by Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad b. ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn on the authority of his father on the authority of his grandfather ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn.

Also (narrated it to me) al-Zuhrī from ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn[9]

This is the only answer chosen by Ibn Isḥāq which he states as fact without betraying that other answers existed.

Where did ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn come to know of this? It is logical to assume that he received this as part of a family tradition from his grandfather, ʿAlī, who was directly involved in the affair.

Confirmation of this comes from an unlikely source.

When Aḥmad b. ʿĪsā (d. 247), the grandson of the martyred Zayd b. ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn, fled to Isfahan in the Caliphate of Hārūn al-Rashīd (d. 193) he narrated some Hadiths there which were picked up by the great Hadith collector Abū Nuʿaym al-Isfahānī (d. 430) and recorded in his Tāʾrīkh.

One of these reads as follows:

Abū Bakr al-Ṭalḥī narrated to us. Abū Ḥuṣayn narrated to us. Abū al-Ṭāhir Aḥmad b. ʿĪsā narrated to us. Al-Ḥusayn b. Zayd[10] narrated to us from ʿAbdallāh b. Muḥammad b. ʿUmar b. ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib from his father (i.e. Muḥammad) from his grandfather (i.e. ʿUmar) from ʿAlī.

He (i.e. ʿAlī) said, “I shrouded the Prophet in three garments: Two Ṣuḥārī[11] garments and a Ḥibara cloak”[12]

This means that the report of ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn should be seen as the report of ʿAlī, a fact that has been missed by all scholars who have discussed this question in the past.[13]

The same answer is corroborated by Ibn ʿAbbās, the other cousin of the Prophet, whose father was also intimately involved in the final rites of the Prophet.

Al-Bayhaqī (d. 458) narrates via his chain to Sufyān al-Thawrī from Ibn Abī Laylā from al-Ḥakam b. ʿUtayba[14] from Miqsam from Ibn ʿAbbās:

The Prophet was shrouded in two white garments and a Ḥibara cloak[15]

Ibn ʿAbbās also reports that his father, al-ʿAbbās, left a waṣiyya that he should be shrouded in a Ḥibara cloak and declared that:

The Messenger of Allah was shrouded in it[16]

A Family Tradition in proto-Sunni Sources

We have seen Ibn Isḥāq’s transmission from ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn. But he is not the only early proto-Sunni authority to transmit information concerning the shroud of the Messenger of Allah from those considered to be Imams by Twelvers.

ʿAbd al-Razzāq al-Ṣanʿānī (d. 211),[17] Ibn Saʿd (d. 230),[18] and Ibn Abī Shayba (d. 235)[19] transmit via their chains to al-Zuhrī (d. 124) from ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn the statement:

كُفِّنَ النَّبِيُّ صلى الله عليه وسلم فِي ثَلَاثَةِ أَثْوَابٍ أَحَدُهَا بُرْد حِبَرَةٌ

kuffina al-nabī fī thalātha athwāb aḥaduhā burd ḥibara

The Prophet was shrouded in three garments one of which was a Ḥibara cloak

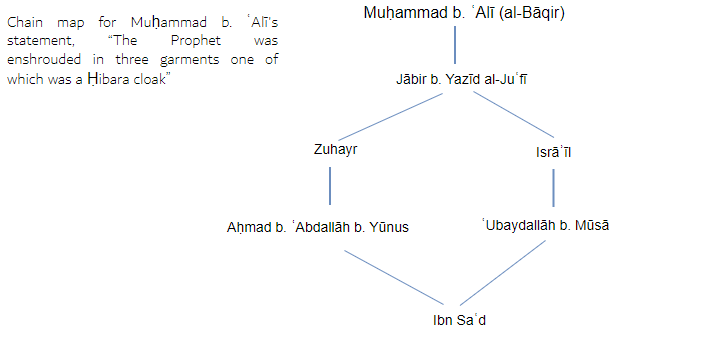

Ibn Saʿd transmits an identical statement via two independent chains that converge at Jābir b. Yazīd al-Juʿfī from Muḥammad b. ʿAlī al-Bāqir (d. 114)[20]

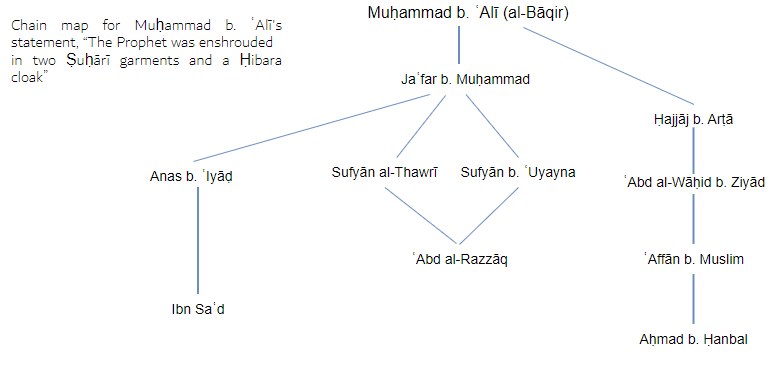

The more complete report transmitted by Ibn Isḥāq is also transmitted by ʿAbd al-Razzāq al-Ṣanʿānī (d. 211)[21], Ibn Saʿd (d. 230)[22] and Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal (d. 241)[23] via their chains to Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq (d. 148) who quotes his father Muḥammad b. ʿAlī al-Bāqir as saying:

كُفِّنَ النَّبِيُّ صلى الله عليه وسلم فِي ثَوْيَيْنِ صُحَارِيَّيْنِ وَثَوْبِ (بُرْدٍ) حِبَرَةٍ

kuffina al-nabī fī thawbayn ṣuḥāriyyayn wa thawb/burd ḥibara

The Prophet was enshrouded in two Ṣuḥārī garments and a Ḥibara cloak

The diagrams speak for themselves.

That the Messenger of Allah was shrouded in this manner is so widely reported from ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn, Muḥammad b. ʿAlī, and Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad, that one can definitively claim that it is historically certain to have been taught by them.

A Family Tradition in Twelver Shia Sources

If the Twelvers’ claim that their corpus preserves authentic material from figures like Muḥammad b. ʿAlī al-Bāqir and Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq is true then we would expect this piece of information to be found therein.

This is exactly what we find to be the case and with even richer detail as can be seen below.

Al-Ṭūsī (d. 460) narrates with a reliable chain to Abū Maryam al-Anṣārī who states that Abū Jaʿfar (i.e. Muḥammad b. ʿAlī al-Bāqir) said:

The Messenger of Allah was shrouded in three garments: A reddish Ḥibara cloak and two white Ṣuḥārī garments …[24]

This is an extremely important report because it confirms that the two Ṣuḥārī garments were white in colour while the Ḥibara cloak was reddish which allows us to make sense of other reports.

Al-Kulaynī (d. 328) narrates with his chain to Zayd al-Shaḥḥām who states that Abū ʿAbdillāh (i.e. Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq) was asked about the shroud of the Messenger of Allah and responded:

In three garments: Two Ṣuḥārī garments and a Ḥibara cloak[25]

Again, al-Ṭūsī narrates with a reliable chain to Samāʿa b. Mihrān who asked al-Ṣādiq a general question about what a dead body should be shrouded in to which the latter responded:

In three garments.

The Messenger of Allah was shrouded in three garments: Two Ṣuḥārī garments and a Ḥibara garment[26]

The unanimity across sectarian lines is striking.

A Sunna that was Practised

We also have evidence that ʿAlī and his descendants took this as a normative precedent which they practiced for their own shrouding.

Al-Kulaynī narrates via his chain of transmission to Abū Maryam al-Anṣārī from al-Bāqir that:

Al-Ḥasan[27] b. ʿAlī shrouded Usāma b. Zayd with a reddish Ḥibara cloak, and ʿAlī shrouded Sahl b. Ḥunayf with a reddish Ḥibara cloak[28]

If there is something we know about Muḥammad b. ʿAlī al-Bāqir it is how stringent he was in following the sunna.[29] It comes as no surprise, then, to find that he instructed his son Jaʿfar to enshroud him in the same.

Ibn Abī Shayba narrates from Ḥafṣ b. Ghiyāth from Jaʿfar from his father (al-Bāqir) that:

The Messenger of Allah was shrouded in two Ṣuḥārī garments and a Ḥibara cloak

Jaʿfar adds:

And my father gave me a waṣiyya to do that (for him)[30]

Al-Bāqir’s waṣiyya was widely known because he sought to make it public information as I have pointed out elsewhere.[31] We find, consequently, that specific details of this waṣiyya have been preserved in both corpuses.

Ibn Saʿd transmits a report which has ʿUrwa b. ʿAbdallāh b. Qushayr asking Jaʿfar ‘what he shrouded his father in’.

Jaʿfar responds:

He gave me waṣiyya (to shroud him) in his qamīṣ (shirt) but that I should cut away its buttons (beforehand); in his ridāʾ (mantle) which he used to wear; and that I buy for him a Yemeni cloak, for the Prophet was shrouded in three garments one of which was a Yemeni cloak[32]

It is the use of this Yemeni or Ḥibara cloak as part of the kafan which is considered a sunna (not the two Ṣuḥārī garments) as is clear from looking at Ibn ʿAbbās’s waṣiyya, what ʿAlī used for Sahl, what al-Ḥasan (or al-Ḥusayn) used for Usāma, and what al-Bāqir is requesting for himself here.

This is duly corroborated in the Shia corpus with even richer detail given as we have come to expect.

Al-Kulaynī narrates via a reliable chain from al-Ḥalabī who quotes al-Ṣādiq as saying:

My father wrote in his waṣiyya that I should shroud him in three garments: one of them a Ḥibara cloak (burd[33]) of his which he used to wear when praying on Friday; another garment; and a qamīṣ (shirt).

I (i.e. Jaʿfar) said to my father, ‘Why are you writing this down?’

He said, ‘I fear that the people might overpower you![34]

And if they say (to you), “Shroud him in four or five (garments)” do not do so!

Fold a turban round (my head), for a turban is not counted as being from the kafan,[35] it is only that which is wrapped around the body which counts.’[36]

Reading ʿUrwa’s proto-Sunni report and al-Ḥalabī’s Shīʿī report side-by-side means we can now identify the unspecified ‘another garment’ in the latter to be a ridāʾ (mantle) with the only slight incongruence being whether the Yemeni/Ḥibara cloak was something that al-Bāqir asked al-Ṣādiq to purchase for him (as per ʿUrwa’s report) or a clothing that he already possessed and used to wear for his prayers on Friday (as per al-Ḥalabī’s report).

This waṣiyya of al-Bāqir was faithfully implemented and we find a Medinan contemporary called Abū Muṣʻab Saʿīd b. Muslim b. Bānak quoted as saying:

I saw upon the dead body of Muḥammad b. ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn a Ḥibara cloak[37]

Sālim, the mawla of ʿAbdallāh b. ʿAlī b. Ḥusayn, confirms that this was a result of a waṣiyya from al-Bāqir that he be ‘shrouded in it’[38]

The cumulative evidence of all that has come above is enough to prove that the position of ʿAlī and his descendants was that the Prophet was shrouded in a Ḥibara cloak (among two other garments).

- The Prophet’s Wife

ʿĀʾisha knows of a Ḥibara cloak associated with the body of the prophet.

As she says in a report transmitted by al-Bukhārī (d. 256):

Abū Bakr came riding on his horse from his lodging in Sunḥ, disembarked and entered the masjid. He did not speak to any of the people and went straight to ʿĀʾisha [i.e. her room]. He headed for the Prophet who was covered with a Ḥibara cloak and uncovered his face. He bent down towards him, kissed him, and began crying. Then he said, ‘May my father be your ransom, O Prophet of Allah, Allah will never give you a second death, as for the death that was decreed for you then you have already experienced it …[39]

Many Hadith collectors narrated the key snippet that has been bolded in truncated fashion devoid of this background context.[40]

One of them is Ibn Abī Shayba who narrates it as follows:

The Messenger of Allah was covered in a Ḥibara cloak

And then comments:

This confirms the statement of ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn[41]

Ibn Abī Shayba believed that this report of ʿĀʾisha supports the one by ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn.

But the issue is that the word used in ʿĀʾisha’s report is sujjiya or musajjā which refers to the act of laying a sheet over the dead body and not necessarily the enshrouding. This is supported by a variant in Bukhārī which has the more explicit verb mughashshā[42]

A Rival Family Tradition

As for ʿĀʾisha’s actual answer on the question of the shroud of the Prophet, Hishām b. ʿUrwa (d. 146) narrates from his father, ʿUrwa b. al-Zubayr (d. 94), who quotes his maternal aunt, ʿĀʾisha, as saying:

كُفِّنَ فِي ثَلَاثَةِ أَثْوَابٍ بِيضٍ سُحُولِيَّةٍ، لَيْسَ فِيهَا قَمِيصٌ وَلَا عِمَامَةٌ

kuffina fī thalātha athwāb bīḍ saḥūliyya/suḥūliyya laysa fīhā qamīṣ wa lā ʿimāma

[The Messenger of Allah] was shrouded in three, white, Saḥūlī/suḥūlī garments. There wasn’t a qamīṣ or a turban among them[43]

This report was transmitted by all the authors of the canonical Sunni Hadith works[44] who present it as the definitive answer to the question of the identity of the shroud of the Prophet.

Put another way, one family tradition (Ḥishām > ʿUrwā > ʿĀʾisha) was given priority over another family tradition (Jaʿfar > al-Bāqir > ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn > ʿAlī).

Comparing the Two

Both ʿAlī and ʿĀʾisha agree that the prophet was shrouded in three garments, but the former describes two of these three garments as Ṣuḥārī (from the town of Ṣuḥār) while ʿĀʾisha describes all three as being سحولية

This last word can be vocalized in two ways.

If the word is vocalized saḥūliyya as the majority do, it would mean that the garments were from the town of Saḥūl in Yemen. This would be a clear contradiction with ʿAlī’s report which has two of them being from Ṣuḥār.

However, vocalizing the word suḥūliyya as a minority do would solve this contradiction.

As Ibn Qutayba (d. 276) used to say:

Suḥūliyya [with a ḍamma on the sīn].

Suḥūl is the plural of saḥl, and it means a white garment[45]

Similarly, the lexicographer Ibn al-Aʿrābī (d. 231) comments that the contested word in ʿĀʾisha’s report means:

Pure white, made exclusively from cotton[46]

In this case, ʿĀʾisha is merely describing the colour of the garments which would mean that the garments could still have been from the town of Ṣuḥār as ʿAlī has it.

To elaborate: When ʿĀʾisha says bīḍ suḥūliyya then suḥūliyya is just an interpretive gloss on bīḍ ‘white’[47] or a duplication for emphasis.[48] This is supported by the fact that some variants of this report drop the word bīḍ[49] while others drop suḥūliyya[50] which indicates that both together can be superfluous; some variants render the disputed word as suḥūl (without the ‘yā’ for nisba)[51] which is unlikely to be referring to a geographical location;[52] and some variants include an additional interpretive gloss min kursuf which means ‘made of cotton’[53]

The only remaining contradiction would be the identity of the third garment which according to ʿAlī was a Ḥibara cloak while ʿĀʾisha asserted that it was just another white cotton garment (indistinctive from the other two).

Who is correct between ʿAlī and ʿĀʾisha? Was the Prophet shrouded in a Ḥibara cloak or not?

Now you See it, Now you Don’t

The fascinating thing is that this contradiction was already known from the very outset.

Abū Dāwūd (d. 275), Tirmidhī (d, 279), Nasāʾī (d. 303) and Ibn Māja (d. 273) narrate with their respective chains to Hishām b. ʿUrwa who reports from his father, ʿUrwa b. al-Zubayr, who reports from his aunt ʿĀʾisha that she said:

The Prophet was shrouded in three, white, Yemeni, garments. There wasn’t a qamīṣ or a turban among them.

This is ʿĀʾisha’s statement that we have come across and are familiar with.

But ʿUrwa adds in this report that the audience who had just heard ʿĀʾisha say this:

Put to her their assertion that it was ‘in two garments and a Ḥibara cloak’

ʿĀʾisha responds:

A cloak was brought but they took it back and did not shroud him in it[54]

It should be evident by now that the allusive ‘their’ refers to ʿAlī and Ibn ʿAbbās. This report proves how early the alternative position was such that ʿĀʾisha was confronted with it and had to respond![55]

What is the story behind the Ḥibara cloak being taken back?

Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal (d. 241) narrates via his chain to Hishām b. ʿUrwa from ʿUrwa from ʿĀʾisha who is quoted as saying:

ʿAbdallāh b. Abī Bakr had given them a Ḥibara ḥulla and the Messenger of Allah was wrapped in it. Then they removed it from him (i.e. the Messenger) and he was shrouded in three, white, garments.

ʿAbdallāh took (back) the ḥulla and said, ‘I will shroud myself in a thing that touched the skin of the Prophet (when I die)’ but he later said, ‘I swear by Allah that I will not be shrouded in a thing that Allah prevented his Prophet from being shrouded in’[56]

The Ḥibara ḥulla mentioned here is evidently the same as the Ḥibara cloak (burd) we have come across throughout this paper.

Even though ḥulla typically refers to a double garment ensemble of an izār (loincloth) and a ridāʾ (mantle) or burd (cloak) together,[57] we are told that each element of this ensemble can also be referred to as ḥulla individually.[58] Thus a single Ḥibara cloak could also be referred to as ḥulla.

We learn from this report that the Ḥibara cloak, which supposedly belonged to ʿĀʾisha’s sibling, ʿAbdallāh b. Abī Bakr, was not just brought but that the Prophet was actually shrouded in it, and then for some unspecified reason it was removed and replaced.

ʿAbdallāh b. Abī Bakr who had donated this garment for the Prophet’s shroud planned to use it for his own shroud, it had touched the body of the big man after all, but later changed his mind reasoning that Allah would have let his Messenger be shrouded in it if it was such a good choice for a shroud.

Muslim (d. 261) provides further detail via his chain to Hishām b. ʿUrwa from ʿUrwa from ʿĀʾisha who is quoted as saying:

The Messenger of Allah was shrouded in three, white, suḥūlī garments made of cotton. There wasn’t a qamīṣ or a turban among them.

As for the ḥulla then what caused people to be confused about it is that it was bought for him (i.e. the Messenger) so that he may be shrouded in it, but the ḥulla was abandoned and he was shrouded in three, white, suḥūlī garments.

Then Ābdallāh b. Abī Bakr took it (i.e. the ḥulla) and said, ‘I will keep it for myself that I may be shrouded in it’, then he (later) said, ‘If Allah, the mighty and majestic, had preferred it for his Prophet he would have shrouded him in it’ so he (i.e. Ābdallāh) sold it and gave the proceeds to charity[59]

So there we have it in black and white. The whole reason some people were mistakenly claiming that the prophet was shrouded in a Ḥibara cloak is down to confusion over something that had occurred. It is true that the Prophet was actually shrouded in it for a time but it was removed and replaced, something which ʿĀʾisha was aware of but which ʿAlī, Ibn ʿAbbās and others somehow did not twig.

As ʿĀʾisha states exultantly when the rival answer was put to her:

We (i.e. I) know better. That ḥulla belonged to ʿAbdallāh b. Abī Bakr. They wanted to shroud him in it but they did not do so. The Messenger of Allah was shrouded in three, white, suḥūlī, garments[60]

This puts the matter to rest, at least in the eyes of the majority of Sunni scholars: ʿĀʾisha has a superior explanation for her rivals’ answer while they are silent about hers.

Al-Dhahabī (d. 748) is pretty representative of this when he says:

As for what Shuʿayb transmitted from al-Zuhrī from ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn that the Messenger of Allah was shrouded in three garments one of which was a Ḥibara cloak, and similar to this was transmitted by Miqsam from Ibn ʿAbbās, then perhaps the one who said that (i.e. ʿAlī and Ibn ʿAbbās) became confused seeing as though the Messenger of Allah was wrapped in a Yemeni ḥulla before it was removed from him[61]

I, on the other hand, would urge caution, for there are discrepancies which appear in ʿĀʾisha’s narrative which need to be explained.

For instance, one report (Muslim’s) has the Ḥibara being bought for the Prophet while another (Aḥmad’s) states that it belonged to ʿAbdallāh b. Abī Bakr.

Even if we put this down to a transmitter’s fallible recollection, ʿĀʾisha claims in one report (Muslim’s) that ʿAbdallāh b. Abī Bakr sold the garment in question after he had changed his mind about using it for his own shroud and gave the amount obtained in charity, but this is contradicted by the report of ʿĀʾisha’s nephew, al-Qāsim b. Muḥammad b. Abī Bakr, given below:

ʿĀʾisha said: The Messenger of Allah was wrapped in a Ḥibara garment, then it was removed from him.

Al-Qāsim said: The remnants of that garment are still with us now[62]

So which one is it: Was the Ḥibara garment sold away and its proceeds given to charity or did it pass down in the safe keep of Abū Bakr’s family?[63]

Reasons for Doubt

But this is not the only problem with ʿĀʾisha’s narrative.

We have independent evidence that the Prophet favoured Ḥibara to be used as a shroud.

Wahb b. Munabbih narrates from Jābir who said:

I heard the Prophet saying, ‘If one of you dies and something (i.e. an amount) is found (i.e. in what he left behind) then he should be enshrouded in a Ḥibara garment[64]

Would the Prophet preach something which he himself does not practice?!

Nor would there be any need for this Ḥibara garment to be bought for the Prophet or for ʿAbdallāh b. Abī Bakr to donate it, since we know that the Prophet owned such clothing, in fact, it was his favourite type of clothing.

Bukhārī reports via his chain to Anas b. Mālik who states:

The garment that the Messenger of Allah most liked to wear was Ḥibara[65]

No wonder we find the Prophet wearing it on special occasions.

ʿAbd al-Razzāq reports from Ibn Jurayj from Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad from Muḥammad b. ʿAlī al-Bāqir that:

The Prophet would wear a Ḥibara cloak of his every Eid day[66]

This same report is also transmitted by the famous jurist al-Shāfiʿī (d. 204) via one intermediary from Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq from his father from his grandfather[67]

That this Ḥibara cloak was ‘reddish’ is confirmed in other reports.

Ibn Saʿd reports via two intermediaries from Ḥafṣ b. Ghiyāth from Ḥajjāj from al-Bāqir from Jābir b. ʿAbdallāh al-Anṣārī that:

The Messenger of Allah would wear his reddish cloak on the two Eids and on Friday[68]

I venture that it is this same reddish Ḥibara cloak which the Prophet wore on special occasions that was used as his shroud, analogous to how al-Bāqir used the Ḥibara he used to wear on Friday for his shroud.

Reception History

It should not escape the attention of the reader that all these reports which have the Prophet being enshrouded with a Ḥibara cloak attributed to ʿAlī, Ibn ʿAbbās, ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn, Muḥammad b. ʿAlī and Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad are only to be found in the pre-canonical collections such as the Ṭabaqāt of Ibn Saʿd and the two Muṣannafs of ʿAbd al-Razzāq and Ibn Abī Shayba which were open to recording a wider range of material from different authorities across several generations.

Indeed, ʿAbd al-Razzāq al-Ṣanʿānī is a notable exception in that he not only transmits such reports but explicitly endorses it as his position. He gives the Zuhrī from ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn report as the 1st report out of a total of 42 reports which he includes in the Bāb al-Kafan (Chapter on Shrouds) before commenting:

This is what is agreed upon and it is what we take[69]

It is not clear whose agreement ʿAbd al-Razzāq has in mind. It is not like he is unaware of the contradicting ʿĀʾisha report which he relegates to 9th place in the chapter,[70] but he clearly prefers the alternative position to it. This is possibly motivated by his pro-Shīʿī sympathies.[71]

However, when we turn our attention to the ‘canonical’ collections we find no traces of this report. The rise of the ‘Ṣaḥīḥ’ movement in Ahl al-Ḥadīth circles meant that alternative reports were disqualified in favour of ʿĀʾisha’s report, either because of perceived weakness of a narrator in the chain or because they terminated at the level of a tābiʿī i.e. ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn.

This is best typified by one of the six canonical authors, al-Tirmidhī (d. 279), who only includes ʿĀʾisha’s report in the relevant chapter, before commenting:

In this chapter (there are relevant reports) from ʿAlī, Ibn ʿAbbās, ʿAbdallāh b. Mughaffal and Ibn ʿUmar.

The Hadith of ʿĀʾisha is a Hadith that is Ḥasan Ṣaḥīḥ

Contradictory reports have been narrated concerning the shroud of the Prophet but the Hadith of ʿĀʾisha is the most authentic of these reports which have been narrated about the shroud of the Prophet.

Action is to be based on the Hadith of ʿĀʾisha per the majority of the people of knowledge (scholars) from among the companions of the Prophet and others[72]

Similarly, Ibn Abd al-Barr (d. 463) comments as follows:

It has been narrated that the Messenger of Allah was shrouded in a Ḥibara cloak and two (other) garments. It has (also) been narrated that he was shrouded in a reddish cloak, and it is said: a black cloak, amongst other alternative opinions that have come down in different Hadiths, none of which can be used as proof because of their disconnection or weakness of most of their chains.

The most authentic (report) concerning the shroud of the Messenger of Allah is the Hadith of ʿUrwa from ʿĀʾisha[73]

Elsewhere he says:

There isn’t in those reports any which can stand in opposition to the Hadith of ʿĀʾisha because of the latter’s strength and the weakness of the chains of all else[74]

The inclusion of ʿĀʾisha’s report in the canonical works means that it became the standard answer agreed upon by all later Sunni scholars when it comes to the question of the shroud of the Messenger of Allah and there is no room for going against this ‘consensus’.

Critical Questions

Should a companion report always and automatically trump a report which stops with a successor, taking for granted the superior knowledge and moral probity of all companions?

Is it really the case that just because ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn does not name his source while speaking about the shroud of the Messenger that his statement should be given zero weight?! This, even when we know from their general practice that individuals like ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn, al-Bāqir and al-Ṣādiq tend to speak authoritatively without giving their source as has happened here?

What if we can infer, as I have attempted to demonstrate, that their source is a family tradition, and a particularly strong one in this particular case, seeing as though it was preserved by more than one branch of the family, repeatedly emphasized by different members of the house, and even put into practice in their daily life as in the waṣiyya of ʿAbbās and al-Bāqir. Doesn’t this count for something?

Moreover, the pre-eminence that ʿĀʾisha’s report on the shroud came to enjoy was a gradual development that only came about with time, especially when this chain (Ḥishām > ʿUrwa > ʿĀʾisha) became favoured by the Ahl al-Ḥadīth, but this was not always the case.

This can be easily demonstrated by noting that authorities among the successors in the generation after the companions such as Saʿīd b. al-Musayyab (d. 94),[75] Ibrāhīm al-Nakhaʿī (d. 96),[76] and Ḥasan al-Baṣrī (d. 110)[77] had their own positions about what the shroud of the Messenger was without giving any precedence to the statement of ʿĀʾisha which they surely must have known of.

Indeed, the famous jurist Abū Ḥanīfa (d. 150) seems to have been influenced by the transmission of the Imams of the Ahl al-Bayt when recommending that a believer’s shroud contain a Ḥibara cloak[78]

What of the discrepancies in ʿĀʾisha’s narrative that I have unearthed here and which no one has resolved satisfactorily, do they not undermine or call into question the pre-eminence that her answer enjoys?

There is also a greater issue at hand which is: wouldn’t the male members, such as ʿAlī and ʿAbbās (whose position is transmitted by his son Ibn ʿAbbās), who actually participated in the shrouding be better suited to know what the shroud was as opposed to a female who has no role in such matters whatsoever.

How could it have escaped their attention that the Ḥibara had been removed after they had wrapped the Prophet in it? Who could have done this when it is unanimously agreed that they, the closest blood-relatives of the Prophet, were the only ones who prepared him for his grave?!

This sentiment was already voiced by certain Hanafi scholars[79]

Abū Layth al-Samarqandī (d. 373) says after noting that the reports of ʿĀʾisha and Ibn ʿAbbās contradict:

The men are the ones who directly partook in that (i.e. enshrouding the Prophet), so they are more knowledgeable about it than women. The reinterpretation of ʿĀʾisha’s report (is to say): There was not among them (the garments in the shroud) a qamīṣ (like that) of the living (i.e. it was modified)[80]

Similarly, ʿAlāʿ al-Dīn al-Kāsānī (d. 587) says:

Taking the report of Ibn ʿAbbās is more justified than taking the report of ʿĀʾisha because Ibn ʿAbbās attended both the shrouding of the Messenger of Allah and his burial while ʿĀʾisha did not. Having said that, the meaning of her statement ‘there wasn’t among them a qamīṣ’ is that ‘a new qamīṣ was not made use of’[81]

Despite casting doubt on ʿĀʾisha’s report, its presence in the canonical works meant that these Hanafi scholars could not reject it outright and a reconciliation was attempted, however far-fetched.

A Metaphor

Once ʿAbbād b. Kathīr (d. after 140), the famous Basran worshipper, and Ibn Jurayj[82] (d. 150), the famous jurist of Mecca, visited Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq (d. 148).

They were conversing when ʿAbbād asked Jaʿfar, ‘In how many garments was the Messenger of Allah shrouded?’

Jaʿfar responded, ‘In three garments: Two Ṣuḥārī garments and a Ḥibara cloak’

ʿAbbād could not hide his aversion at this and exclaimed ‘You do not cease narrating to us hadiths which are contrary to what we have heard!’

Jaʿfar replied with a cryptic remark:

Mary’s date palm (i.e. from which she ate) was ʿajwa (the highest quality variety of dates) and it descended from heaven, so that which is planted from the original will also produce ʿajwa, while that which is planted from left-over pickings will only produce lawn (the lowest quality variety of dates)!

This marked the end of the conversation and the duo exited. ʿAbbād wondered aloud what to make of this last statement which he was sure held a message meant for them. Ibn Jurayj directed him to ask a youth (i.e. Maymūn al-Qaddāḥ) who had attended the gathering for he ‘was among them’ i.e. the disciples of Jaʿfar.

When they ask Maymūn, the latter quips ‘Could you really not tell what he meant?’ and proceeds to explain:

He set forth a parable of his own person for you! He informed you that he is a descendant from the descendants of the Messenger of Allah and the knowledge of the Messenger of Allah is with them, so what issues forth from them then that is correct, and what issues forth from other than them is not but left-overs[83]

It is my sincere appeal to the reader to not forgo ʿajwa for the sake of lawn!

Conclusion

This paper proves the importance of reading the Sunni and Shia corpus side-by-side because the two were in conversation and can help illuminate each other. Such a study will confirm how reliable information from the Ahl al-Bayt came to be sidelined, not necessarily because of some mendacious design, but because of the imposition of anachronistic standards e.g. connectivity of the ‘chain’.

Not all is lost, however, for there is growing evidence to confirm the authentic preservation of the teachings of the Imams of the Ahl al-Bayt in the Shia corpus whose theological underpinnings meant that they gave precedence to the statements of these Imams above all else and strived to codify them. It is only hoped that the strait-jacket of the Sunni canon will not limit the ability of neutral researchers in reaching the correct answer, be it in the problem discussed here or any other.

Footnotes

[1] Al-Qurṭubī (d. 671) says it was called ḥibara from taḥbīr which means ‘embellish’ or ‘decorate’. See Fatḥ al-Bārī, v. 10, p. 277 (https://shamela.ws/book/1673/6038).

[2] The famous Ṣuḥār even down to the present day is the town in Oman, but there was was a locality with the same name in Yemen to which the clothes are attributed. See Al-Nihāya fī Gharīb al-Ḥadīth wa-l-Athar, v. 3, p. 12 (https://shamela.ws/book/23691/1000).

[3] Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 2, p. 245-251 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/725).

[4] Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 2, p. 251 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/731)

[5] Notably a descendant of al-ʿAbbās by the name of al-Ḥusayn b. ʿAbdallāh b. ʿUbaydallāh b. al-ʿAbbās b. ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib who has been severely weakened by some Sunni Hadith critics.

[6] The recension of Ibn Hishām in Al-Sīra al-Nabawiyya, v. 2, p. 662 (https://shamela.ws/book/23833/1399); Tāʾrīkh al-Ṭabarī, v. 3, pp. 211-212 (https://shamela.ws/book/16953/38997) where the Kathīr (sic.) b. ʿAbdallāh in the chain should be corrected to Ḥusayn b. ʿAbdallāh. See also Musnad Aḥmad, v. 4, pp. 186-187, n. 2357 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/1696) who combines three consecutive but separate accounts given by Ibn Isḥāq into a single running narration, giving the chain for the last part to the whole. Are we sure the Ahl al-Ḥadīth were better at this than the Akhbārīs?!

[7] Ibid.

[8] This statement was censored by Ibn Hishām but can be found in Ṭabarī’s transmission of Ibn Isḥāq’s original. See Tāʾrīkh al-Ṭabarī, v. 3, p. 212 (https://shamela.ws/book/9783/1486).

[9] Al-Sīra al-Nabawiyya, v. 2, p. 663 (https://shamela.ws/book/23833/1400). See also al-Bayhaqī in his Sunan al- Kubrā, v. 7, p. 239-240, n. 7659 (https://shamela.ws/book/148486/3946) and al-Ṭabarī in his Tāʾrīkh, v. 3, p. 212 (https://shamela.ws/book/9783/1486).

[10] It is pertinent to mention here that this Ḥusayn was brought up and cared for by Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq after the martyrdom of his father Zayd. See Rijāl al-Najāshī, p. 52, n. 115 (https://lib.eshia.ir/14028/1/52).

[11] Reading ‘Ṣuḥāriyyayn’ here per the variant of this report in Al-Kāmil fī Ḍuʿafāʾ al-Rijāl, v. 3, p. 218 (https://shamela.ws/book/12579/1220).

[12] Tāʾrīkh Iṣbahān, v. 1, p. 111 (https://shamela.ws/book/1714/274).

[13] The scholars have overlooked this report, which is only found in an obscure work, in favour of a more well-known report attributed to ʿAlī: ʿAbdallāh b. Muḥammad b. ʿAqīl narrates from Ibn al-Ḥanafiyya who narrates from his father, ʿAlī, that, “The Prophet was shrouded in seven garments”. See Musnad Aḥmad, v. 2, p. 132, n. 728 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/668); ibid., v. 2, p. 182, n. 801 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/718); Muṣannaf Ibn Abī Shayba, v. 6, p. 503, n. 11409 (https://shamela.ws/book/333/12967). The fact that the Twelver Imams unanimously support the lesser-known report, as becomes clear in this paper, means that the Ibn al-Ḥanafiyya report must be considered shaadh (aberrant).

[14] This is what al-Ḥakam narrates from Miqsam from Ibn ʿAbbās. But the weak narrator Yazīd b. Abī Ziyād narrates something completely different from Miqsam from Ibn ʿAbbās: ‘The Messenger of Allah was shrouded in three garments: The qamīṣ that he died in and a [reddish] Najrānī ḥulla which he used to wear’ with a ḥulla counting as two garments. See Musnad Aḥmad, v. 3, p. 414, n. 1942 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/1419); Muṣannaf Ibn Abī Shayba, v. 6, p. 494, n. 11370 (https://shamela.ws/book/333/12928); Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 2, p. 250 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/730); Sunan Abī Dāwūd, v. 5, p. 67, n. 3153 (https://shamela.ws/book/117359/2651); Sunan Ibn Māja, v. 1, p. 472, n. 1471 (https://shamela.ws/book/1198/1920); Musnad Abī Yaʿla, v. 5, p. 63, n. 2655 (https://shamela.ws/book/12520/2704). I obviously prefer al-Ḥakam’s transmission over Yazīd’s.

[15] Al-Sunan al-Kubrā, v. 7, p. 239, n. 6758 (https://shamela.ws/book/148486/3945). A version of this report transmitted by Ibn Saʿd has the wording ‘reddish cloak’ as opposed to ‘Ḥibara cloak’. See Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 2, p. 248 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/728). Note that the two Ṣuḥārī garments were white in colour and the Ḥibara cloak was reddish in colour as will be demonstrated in this paper (see the report referenced in footnote 24), so there is no contradiction. See also ʿAbd al-Razzāq in his Muṣannaf, v. 4, p. 151, n. 6356 (https://shamela.ws/book/84/1798) and from him Aḥmad in his Musnad, v. 5, p. 53, n. 2861 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/2061) but read ‘thawbayn abyaḍayn’ for ‘burdayn abyaḍayn’ as is correctly quoted by Ibn Kathīr in his Al-Bidāya wa-l Nihāya, v. 8, p. 129 (https://shamela.ws/book/4445/4268).

[16] Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 4, p. 30 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/1414).

[17] Al-Muṣannaf, v. 4, p. 151, n. 6353 & 6354 (https://shamela.ws/book/84/1798).

[18] Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 2, pp. 247-248 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/728)

[19] Al-Muṣannaf, v. 6, p. 501, n. 11398 (https://shamela.ws/book/333/12956)

[20] Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 2, p. 248 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/728)

[21] Al-Muṣannaf, v. 4, p. 151, n. 6357 (https://shamela.ws/book/84/1798); Al-Muṣannaf, v. 4, p. 199, n. 6574 (https://shamela.ws/book/84/1846) where al-Bāqir gives extra detail: “The Prophet died on a Monday. He was not buried that day nor that night, until it was towards the end of Tuesday. He was given ghusl with his qamīṣ on him. He was shrouded in three garments: Two Ṣuḥārī garments and a Ḥibara cloak. He was prayed over without an Imam …”

[22] Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 2, p. 248 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/728).

[23] Al-Musnad, v. 4, p. 139, n. 2284 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/1649). Note that Ḥajjāj also narrates the same from al-Ḥakam from Miqsam from Ibn ʿAbbās. The wording of this report is ‘two white garments and a red cloak’ but that this red cloak is our Ḥibara as will be demonstrated (see the report referenced in footnote 24)

[24] Tahdhīb al-Aḥkām, v. 1, p. 296, n. 37/869 (https://lib.eshia.ir/10083/1/296).

[25] Al-Kāfī, v. 5, p. 377, n. 2/4339 (https://lib.eshia.ir/27311/5/377).

[26] Tahdhīb al-Aḥkām, v. 1, p. 291, n. 18/850 (https://lib.eshia.ir/10083/1/291).

[27] ‘Al-Ḥasan’ here is likely a scribal error for ‘al-Ḥusayn’ since most historians have Usāma b. Zayd dying a few years after the death of al-Ḥasan in the year 50.

[28] Al-Kāfī, v. 5, p. 395, n. 9/4369 (https://lib.eshia.ir/27311/5/395). See also the ending of the lengthier report in Tahdhīb al-Aḥkām, v. 1, p. 296, n. 37/869 (https://lib.eshia.ir/10083/1/296) with a reliable chain to Abū Maryam. See also Rijāl al-Kashshī, v. 1, p. 39, n. 80 (https://lib.eshia.ir/10241/1/39) [where Sahl b. Zādhawayh in the chain should be corrected to Sahl b. Ziyād] and Rijāl al-Kashshī, v. 1, p. 36, n. 73 (https://lib.eshia.ir/10241/1/36).

[29] Zurāra quotes al-Bāqir as saying, “Verily I detest it for a man to prefer something over the sunna of the Messenger of Allah or to abandon it!” See Al-Kāfī, v. 6, p. 226, n. 10/5108 (https://lib.eshia.ir/27311/6/226).

[30] Al-Muṣannaf, v. 6, p. 494, n. 11372 (https://shamela.ws/book/333/12930). See also the report of Anas b. ʿIyāḍ in Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 2, p. 248 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/728) where al-Ṣādiq quotes the description of the Prophet’s shroud from his father before stating, “And my father gave me waṣiyya to do the same (for him) and said, ‘Do not add beyond that a thing!’”

[31] In my article ‘How to Know your Imam (pt. I)’ (https://shiiticstudies.com/2022/01/22/how-to-know-your-imam-pt-i/). The waṣiyya and the waṣī who was to enact it were both publicized as a means for the early Shia to recognize their Imam in cases of succession disputes.

[32] Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 7, p. 317 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/3057).

[33] All the manuscripts of Al-Kāfī have ridāʾ here but I follow al-Ṣadūq who renders it as burd when quoting it. See Man lā Yaḥḍuruhu al-Faqīh, v. 1, p. 153, n. 421 (https://lib.eshia.ir/11021/1/153). And this is surely correct in light of all that we have seen. It is unfortunate that no scholar in the long reception history of Al-Kāfī has, to my knowledge, proposed this emendation!

[34] This enigmatic statement can be understood in light of ʿAbd al-Aʿlā’s key report discussed in the aforementioned article (see footnote 31) which similarly goes over al-Bāqir’s waṣiyya. We learn that al-Bāqir, and when he was about to die, called four prominent residents of Medina who were not of the Shia (including Nāfiʿ, the mawla of Ibn ʿUmar) and dictated his waṣiyya to his son Jaʿfar in their presence thereby identifying him as his waṣī publicly. The document read, ‘Muḥammad b. ʿAlī gives waṣiyya to his son Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad and instructs him to shroud him in his burd which he used to wear for his Friday prayers, to fold a turban around him, to make his grave rectangular (four-sided), to raise it to the height of four fingers, and then to leave him be.’ When al-Ṣādiq later asks his father why he called in witnesses for something as banal as this, al-Bāqir elaborates: ‘I did not want you to be vanquished (i.e. by other pretenders), and that it be said “so-and-so did not leave a waṣiyya”, so I wanted it to be a ḥujja (proof) for you, and that (i.e. the ḥujja) is when someone comes to a town and inquires “who is the waṣī of so-and-so” it is said “so-and-so.”’ See Al-Kāfī, v. 2, pp. 269-272 (at 271), n. 2/987 (https://lib.eshia.ir/27311/2/269).

[35] It is a sunna to make the garments used for the kafan odd, specifically, three in number. There is debate in Sunni fiqh about whether the turban should be counted as part of this or not. The Imam reveals an important principle which excludes the turban from the count (since it is not used to wrap the body).

[36] Al-Kāfī, v. 5, pp. 380-381, n. 7/4344 (https://lib.eshia.ir/27311/5/380). See also Al-Kāfī, v. 5, pp. 366-367, n. 3/4334 (https://lib.eshia.ir/27311/5/366) for a variant of the same report.

[37] Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 7, p. 318 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/3058).

[38] Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 7, p. 317 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/3057).

[39] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, v. 2, p. 217, n. 1250-1251 (https://shamela.ws/book/1284/903); Musnad Aḥmad, v. 41, p. 355, n. 24863 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/21007). See for the same account Muṣannaf ʿAbd al-Razzāq, v. 4, pp. 309-310, n. 6984 (https://shamela.ws/book/84/1957) [from whence Aḥmad in his Musnad, v. 5, p. 208, n. 3090 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/2216)] and with significant additional content, ibid., v. 6, p. 89, n. 10617 (https://shamela.ws/book/84/2817), but note that the one narrating it here is Ibn ʿAbbās instead of ʿĀʾisha!

[40] Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 2, p. 231 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/711); Muṣannaf ʿAbd al-Razzāq, v. 4, p. 153, n. 6364 (https://shamela.ws/book/84/1800); Musnad Aḥmad, v. 41, pp. 128-129, n. 24581 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/20780); Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, v. 7, p. 427, n. 5815 (https://shamela.ws/book/1284/3755); Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, v. 2, p. 651, n. 48/942 (https://shamela.ws/book/1727/2116).

[41] Al-Muṣannaf, v. 6, p. 501, n. 11399 (https://shamela.ws/book/333/12957).

[42] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, v. 5, p. 476, n. 4432-4433 (https://shamela.ws/book/1284/2761).

[43] Al-Muwaṭṭāʾ, v. 1, p. 223, n. 5 (https://shamela.ws/book/1699/682). See also: Muṣannaf ʿAbd al-Razzāq, v. 4, p. 152, n. 6362 (https://shamela.ws/book/84/1799); Musnad Aḥmad, v. 42, p. 198, n. 25323 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/21369); ibid., v. 42, p. 385, n. 25601 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/21556).

[44] For instance, Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, v. 2, pp. 232-233, n. 1282, 1283, 1284 (https://shamela.ws/book/1284/918); Sunan Abī Dāwūd, v. 5, p. 66, n. 3151 (https://shamela.ws/book/117359/2650).

[45] Quoted by Ibn al-Jawzī (d. 597) in his Kashf al-Mushkil min Ḥadīth al-Ṣaḥīḥayn, v. 4, p. 317 (https://shamela.ws/book/5906/2002). Al-Zamakhsharī (d. 538) discusses why a nisba to the plural (suḥūl) instead of the singular (saḥl) would have come about for this case despite it not being the norm. See al-Fāʾiq fī Gharīb al-Ḥadīth, v. 2, p. 159 (https://shamela.ws/book/7015/598).

[46] Quoted by Abū ʿUbayd al-Harawī (d. 401) in his Al-Gharībayn fī al-Qurʾān wa-l-Ḥadīth, v. 3, p. 874 (https://shamela.ws/book/16782/825).

[47] Or more likely, bīḍ is an interpretive gloss on the rarer word suḥūliyya, and this is borne out by reports in which suḥūliyya is named first before bīḍ. See for example, Muṣannaf ʿAbd al-Razzāq, v. 4, p. 152, n. 6361 (https://shamela.ws/book/84/1799).

[48] Qāḍī ʿIyāḍ (d. 544) notes that it is not strange for Arabs to say the same thing using two different words for emphasis and gives an example from the Qur’an 35:27. See Ikmāl al-Muʿallim bi-Fawāʾid Muslim, v. 3, p. 393 (https://shamela.ws/book/122406/1678).

[49] Musnad Aḥmad, v. 42, p. 198, n. 25323 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/21369); Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, v. 2, p. 650, n. 47/941 (https://shamela.ws/book/1727/2115) with a different chain to ʿĀʾisha.

[50] Musnad Aḥmad, v. 42, p. 521, n. 25795 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/21692); Sunan al-Nasāʾī, v. 4, p. 58, n. 1899 (https://shamela.ws/book/1339/1447).

[51] Muṣannaf ʿAbd al-Razzāq, v. 4, p. 152, n. 6362, (https://shamela.ws/book/84/1799); Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, v. 2, p. 232, n. 1282 (https://shamela.ws/book/1284/918); Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, v. 2, p. 650, n. 46/941 (https://shamela.ws/book/1727/2113).

[52] Refer to al-Kirmānī (d. 786) who explains that such usage while possible would be ineloquent. See Al-Kawākib al-Durārī fī Sharḥ Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, v. 7, p. 72 (https://shamela.ws/book/13605/1408).

[53] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, v. 2, pp. 228-229, n. 1275 (https://shamela.ws/book/1284/915).

[54] Sunan al-Tirmidhī, v. 2, p. 484, n. 1017 (https://shamela.ws/book/1363/1161); Sunan Abī Dāwūd, v. 5, p. 67, n. 3152 (https://shamela.ws/book/117359/2651); Sunan al-Nasāʾī, v. 4, p. 58, n. 1899 (https://shamela.ws/book/1339/1447); Sunan Ibn Māja, v. 2, p. 451, n. 1469 (https://shamela.ws/book/98138/1020). In a variant of this report, ʿUrwa is quoted as saying, “We said to ʿĀʾisha: ‘They assert that he was shrouded in a Ḥibara cloak’”. See Muṣannaf Ibn Abī Shayba, v. 6, p. 493, n. 11369 (https://shamela.ws/book/333/12927).

[55] It is also possible that ʿUrwa ‘grafted’ this addition to his aunt’s original report as a way of explaining away the discrepancy between his tradition and that promulgated by his contemporary ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn.

[56] Musnad Aḥmad, v. 41, pp. 464-465 (at 465), n. 25005 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/21117); Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 3, pp. 184-185 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/995). See a shorter truncated report which is mawqūf at Hishām b. ʿUrwa in Muṣannaf ʿAbd al-Razzāq, v. 4, pp. 152-153, n. 6363 (https://shamela.ws/book/84/1799) where the clothing in question is called ‘thawb ḥibara’ or ‘Ḥibara garment’ instead of ḥulla.

[57] Refer to Khalīl (d. 170) who says, ‘al-ḥulla izār wa ridāʿ burdun aw ghayruh’. See Kitāb al-ʿAyn, v. 3, p. 28 (https://shamela.ws/book/1682/727).

[58] This is the position of Ibn al-Aʿrābī (d. 231) who says, ‘yuqāl li-l izār wa-l-ridāʿ ḥulla wa likkul wāḥid minhumā ʿalā infirādihi ḥulla’. See Tahdhīb al-Lugha, v. 3, p. 283, (https://shamela.ws/book/7031/842). This is pace Abū ʿUbayd (d. 224) who says, ‘lā tusammā ḥulla ḥattā takūn thawbayn’. See Gharīb al-Ḥadīth, v. 1, p. 285 (https://shamela.ws/book/32196/171).

[59] Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, v. 2, p. 649, n. 45/941 (https://shamela.ws/book/1727/2112).

[60] See Al-Tamhīd, v. 14, p. 93 (https://shamela.ws/book/236/7720). The report begins quite obscurely ذُكِر لعائشةَ ‘it was put to ʿĀʾisha’ without clarifying what exactly was put to her. But notice the startling similarity with the wording of the other report فذُكِرَ لعائشة قولُهم في ثوبين وبُرْدِ حِبَرَة ‘It was put to ʿĀʾisha their assertion that it was in two garments and a Ḥibara cloak’ (refer to footnote 54) which tells me that the two are describing the same incident, in which case ʿĀʾisha bringing up ḥulla in the response to a question about the burd is further evidence that ḥulla and burd are interchangeable.

[61] Siyar Aʿlām al-Nubalāʾ (Al-Sīra al-Nabawiyya), v. 2, p. 479 (https://shamela.ws/book/10906/1137).

[62] Musnad Aḥmad, v. 42, p. 166, n. 25280 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/21337).

[63] Al-Bayhaqī is the only scholar I have seen who recognized this contradiction and attempted to advance a solution. His solution is to propose that the Ḥibara ḥulla that ʿAbdallāh b. Abī Bakr sold off and gave the proceeds to charity was different from the Ḥibara burd that al-Qāsim says they still have the remnants of. In other words, the Prophet was enshrouded in a Ḥibara ḥulla which was then removed and also shrouded in a different Ḥibara cloak which was also removed. This is farcical. My solution is to assert that the same Ḥibara garment was at times referred to as burd and at others ḥulla (something which is linguisticallya acceptable). The obvious flaw in Bayhaqī’s creative solution is that there exists no single report which speaks of two separate ‘removals’. All such reports are therefore speaking of the same incident. See Suna al-Kubrā, v. 7, pp. 242-243 (https://shamela.ws/book/148486/3948).

[64] Sunan Abī Dāwūd, v. 5, p. 66, n. 3150 (https://shamela.ws/book/117359/2650); The report is corroborated by Abū al-Zubayr who narrates it from Jābir. See Musnad Aḥmad, v. 22, pp. 451-452, n. 14601 (https://shamela.ws/book/25794/11103).

[65] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, v. 7, p. 427, n. 5814 (https://shamela.ws/book/1284/3755).

[66] Al-Muṣannaf, v. 3, p. 479, n. 54821 (https://shamela.ws/book/84/1576).

[67] Musnad al-Shāfiʿī, v. 2, p. 42, n. 473 (https://shamela.ws/book/9615/249).

[68] Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 1, pp. 387-388 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/433). Note a similar report but mawqūf at al-Bāqir on the same page. Al-Ṭabarānī narrates a similar report via his chain to Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq from his father al-Bāqir from his father ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn from Ibn ʿAbbās. See Al-Muʿjam al-Awsaṭ, v. 7, p. 316, n. 7609 (https://shamela.ws/book/28171/7948).

[69] Al-Muṣannaf, v. 4, p. 151, n. 6353 (https://shamela.ws/book/84/1798).

[70] Al-Muṣannaf, v. 4, p. 152, n. 6361 (https://shamela.ws/book/84/1799).

[71] See my article: https://shiiticstudies.com/2022/11/17/%ca%bfabd-al-razzaqs-shi%ca%bfism-and-the-limits-of-sunni-hadith-criticism/

[72] Sunan al-Tirmidhī, v. 2, p. 485, n. 1018 (https://shamela.ws/book/1363/1162).

[73] Al-Istidhkār, v. 3, pp. 3-4 (https://shamela.ws/book/1722/1061).

[74] Al-Istidhkār, v. 3, p. 15 (https://shamela.ws/book/1722/1073).

[75] It is reported from Saʿīd that the Messenger of Allah was, ‘enshrouded in three garments one of them a cloak’. See Muṣannaf Ibn Abī Shayba, v. 6, p. 501, n. 11400 (https://shamela.ws/book/333/12958). Ibn Saʿd also transmits via 4 separate chains from Qatāda from Saʿīd that the Messenger of Allah was, ‘enshrouded in two sheets and a Najrānī cloak’. See Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 2, p. 247 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/727). If the two sheets are considered to be the two Ṣuḥārī garments and if Najrānī = Yemeni then Saʿīd b. al-Musayyab’s position would be identical to ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn and the Imams of Ahl al-Bayt.

[76] It is reported from Ibrāhīm that the Messenger of Allah was, ‘enshrouded in a Yemeni ḥulla and a qamīṣ’. See al-Shaybānī’s Al-Āthār, v. 2, p. 27, n. 228 (https://shamela.ws/book/1332/293). Ibn Saʿd transmits the same via 3 different chains from Ibrāhīm. See Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 2, p. 249 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/729).

[77] It is reported from al-Ḥasan that the Messenger of Allah was, ‘enshrouded in a Coptic (garment) and a Ḥibara ḥulla’. See Al-Ṭabaqāt, v. 2, p. 249 (https://shamela.ws/book/146/729).

[78] Abū Ḥanīfa’s position is paraphrased as follows: ‘If a man is enshrouded in three garments, one of them a Ḥibara, and the other two white in colour then that is preferable’. See Ibn Hubayra’s (d. 560) Ikhtilāf al-Aʾimma al-ʿUlamāʾ, v. 1, p. 179 (https://shamela.ws/book/6228/163).

[79] The Hanafi scholars were motivated by defending the position of their madhhab which recommended shrouding in a qamīṣ, something which ʿĀʾisha’s report contradicted.

[80] Mukhtalaf al-Riwāya (ed. Maktabat al-Rushd, 1426), v. 1, pp. 508-509, n. 318.

[81] Badāʾiʿ al-Ṣanāʾiʿ, v. 1, p. 306 (https://shamela.ws/book/8183/305).

[82] All the manuscripts of Al-Kāfī have Ibn Shurayḥ which Majlisī and other commentators have a hard time identifying. I have corrected it to Ibn Jurayj as per the variant of this report found in the Aṣl of ʿĀṣim b. Ḥumayd and this is consistent with him being described as ‘faqīh ahl makka’. Note that he is also referred to by the kunya Abū al-Walīd in the Aṣl which is known to be the kunya of Ibn Jurayj.

[83] Al-Kāfī, v. 2, pp. 329-330, n. 6/1052 (https://lib.eshia.ir/27311/2/329); Al-Uṣūl al-Sitta ʿAshar (Aṣl ʿĀṣim b. Ḥumayd), v. 1, pp. 172-173, n. 71/124 (https://lib.eshia.ir/86022/1/172). Notice that the report in the Aṣl is inferior in many respects when compared to the lengthier version found in Al-Kāfī. For example, it does not contain the explanation of the metaphor. Indeed, there are parts of the report in the Aṣl, like the sudden appearance of Maymūn who had not been introduced before, which mean that it is unintelligible without making reference to Al-Kāfī. This demonstrates to me the antiquity of the Aṣl (i.e. that the Aṣl is very early) and not the work of a later fabricator who must have had access to Al-Kāfī. This is a fāʾida which I have not seen advanced before. All praise belongs to Allah!